|

| Tirailleurs Sénégalais in France, 1917 (okayafrica.com) |

My previous post touched on African troops in French service. Of course, France was not the only country to employ Black troops (either colonials or home-country citizens).

This paper by Christian Koller examines the African contingents in various armies, Europeans' perceptions of them, and the effect of the war on these participants and their cultures.

Papers at this conference explored some of the same themes. And another page includes

some rare and fascinating photos of Black soldiers in the British and German regular armies (rather than in colonial units).

British African Troops

|

| King's African Rifles corporal and privates (okayafrica.com) |

The title of "most famous African unit" to serve in the British forces in the Great War undoubtedly belongs to the

King's African Rifles. Originally raised and serving as gendarmes (units with both civil police and military responsibilities), the KAR was expanded again and again during the Great War as the activities of Germany's colonial forces in German East Africa kept the British forces scrambling. By 1918, the KAR consisted of 22 battalions, well over 30,000 men. Disease had claimed an additional 3,000 men and combat more than 5,100 either killed or wounded. The KAR was originally formed in 1902 and replaced a number of other localized units from Kenya, Ugnada, British Somaliland, and Nyasaland (present-day Malawi). The KAR continued in their role as gendarmerie after the war and served around the globe in World War Two, continuing their reputation as brave and skillful fighters.

Other African units, which together made up the

West African Frontier Force, were the

Gold Coast Regiment, the

Nigeria Regiment, the Sierra Leone Battalion, and the Gambia Company. Another unit from East Africa was the

Somaliland Camel Corps.

|

| Men of the South African Native Labour Contingent (Mail & Guardian) |

South Africans had mixed feelings about the war. Some attempted to overthrow the Union government, and though the initial coup failed, an armed uprising persisted for nearly a year. South African forces fought for Britain in German Southwest Africa and in East Africa; a brigade-sized contingent even served in Egypt and on the Western Front. But only White South Africans were allowed to serve under arms. Black and mixed-race South Africans were only permitted to serve as porters and labourers or in France in the South African Native Labour Contingent, part of the

Labour Corps.

Rhodesia (technically two entities, Northern and Southern Rhodesia, both controlled by the British South Africa Company, rather than by the Crown or a dominion government) did not share South Africa's equivocal feelings about the war. Many White Rhodesians joined the British Army or the Royal Flying Corps directly, sometimes forming formal or informal Rhodesian subunits. Others volunteered for the 1st and later 2nd Rhodesian Regiments, all-White units that served in South Africa during the tail end of the rebellion there, then in Southwest Africa and in East Africa.

|

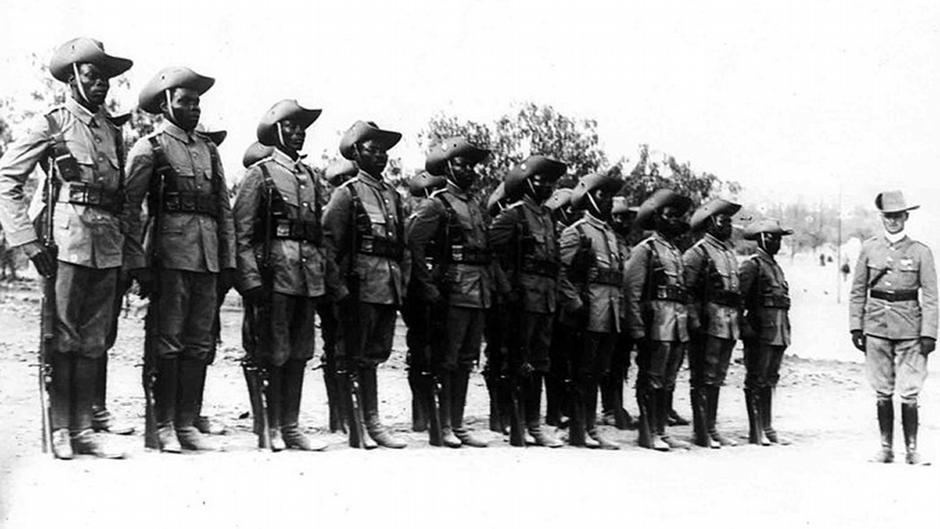

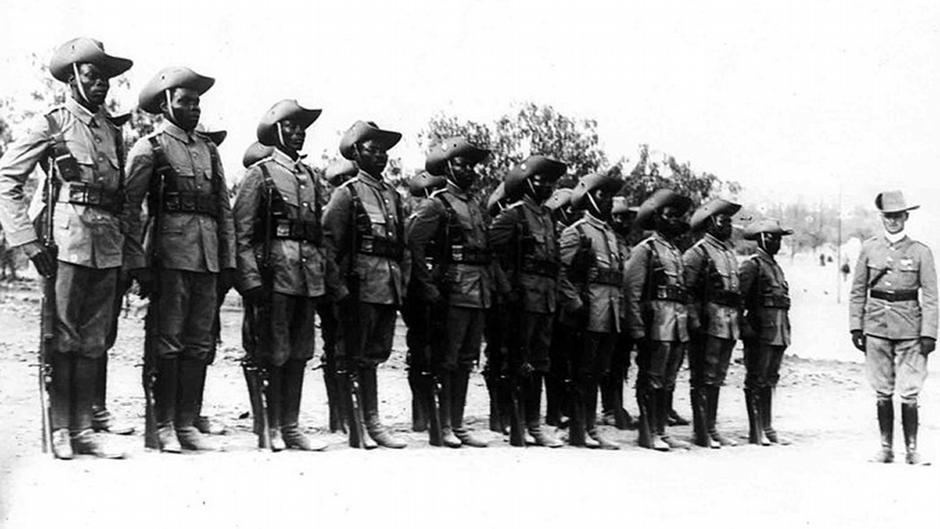

| The Rhodesia Native Regiment on parade in Salisbury (Wikipedia) |

Rhodesia also raised first one then two Black African battalions (still led by White officers) for what was eventually called the

Rhodesia Native Regiment. These troops served through arduous conditions and with great bravery in the East African campaign. When a contingent of 500 RNR soldiers, discharged and on their way home at the end of the war, reached the capital, Salisbury, they were greeted by a huge celebration, including the senior government minister, the territorial administrator, who gave a speech thanking the troops for their service and crediting them for having helped win the war.

But without question the largest force raised in Africa by the British

was the conscripted labour force that supported British operations, the

Carrier Corps of 400,000 men from East and Central Africa.

British West Indians

Of course, one significant Black contingent in the British forces were not

Africans but troops from the West Indies. The

British West Indies Regiment contributed eleven battalions to serve in Europe, in Italy, West and East Africa, and

in Egypt and Palestine over the course of the war. The

Bermuda Militia Artillery sent contingents to the Western Front with the Royal Garrison Artillery. (The Bermuda Volunteer Rifle

Corps, a white unit, also served on the Western Front). And civilians

contributed to war loans, bond appeals, and other fund-raising drives,

contributing considerable sums especially to the air services. One

Caribbean soldier,

George Blackman, interviewed in 2002, recounted some of his experiences of harsh labour and sporadic combat.

Black Britons

|

| Arthur Roberts, RSF (The History Press) |

And perhaps the smallest, but by no means the least Black contingent in the British forces were those Black Britons who served in the Army, the Royal Navy, and other services lke the merchant marine. The

footballer Walter Tull, probably the most famous of these, enlisted, served in France, was commissioned as an officer in the Middlesex Regiment, but was sadly killed in action in 1918. This

article from BBC Magazine relates the story of David Louis Clemetson, a Cambridge law student who served as a commissioned officer in the Territorials in Macedonia, then transferred into the Welsh Regiment. He, too, was killed in action in France in 1918.

The story of Arthur Roberts, who served in the Kings Own Scottish Borderers and the Royal Scots Fusilier, was a happier one; he survived the war to be demobilized, become a skilled tradesman, marry and raise a family, dying only in 1982. For a general study of Black British experiences of the war, military and civilian,

Black Poppies: Britain’s Black Community and the Great War seems to be the most recent and comprehensive account. It is available as

a Google eBook, as well as in print.

Belgium and Others

Belgium's

Force Publique, another gendarme force with White officers and NCOs and African private soldiers, expanded during the war as it fought the Germans in West, Central, and East Africa. Starting 1914 with 17,000 men in four battalions, the FP expanded to about 25,000 men in 1916 and to 15 battalions by the end of the war with another 260,000 men conscripted as bearers.

Portugal and Spain also raised askari (native troops) in their Saharan and sub-Saharan African colonies, but these saw little action in the war.

Germany

|

| Kamerun Schutztruppen (Deutsche Welle) |

On the German side, the

Schuztruppe ("protection force") of the colonies of German West Africa, German Southwest Africa, and German East Africa numbered over 6,300 men, including medical and technical staff. Each colony had slightly different policies; in Southwest Africa, because of Germany's genocidal war with the native Herero population, all ranks in the Schutztrruppe were White--either Germans or disaffected Boers. In West Africa (Kamerun and Togoland), Whites provided the officers and NCOs and Blacks the enlisted ranks.

|

| Schutztruppe soldier saying goodbye to his family (okayafrica.com) |

In East Africa, the 14 companies of Schutztruppen included White officers and technical staff, some White NCOs and technicians, but also Black NCOs (three times as many as White ones) and Black other ranks. Each company also had a body of 250 bearers. Companies also had irregular native contingents, called Ruga-Ruga, of comparable size to the companies (150-200 men). An additional 16 companies were raised during the war, as well as eight companies of riflemen (

Schützenkompagnies) which were originally formed by White settlers but became of mixed racial composition as time went on. Sometimes numbering only a few thousand men, the

Deutsch-Ostafrika Schutztruppen eventually required close to a quarter of a million British, Indian, and African troops to be posted to the East African theater. At the end of the war, the DOS was still operating in the field, undefeated and uncaptured. When news of the armistice in Europe reached them, they laid down their arms. In 1919, they were honored with a march through the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin (only officers were able to participate, as the troops had been demobilized in Africa). In 1964, the German government voted to provide back-dated pay to all askaris (native troops) of the Schutztruppe who could present proof of service. As a commmentor to the previous post noted, the test that was eventually settled on was asking the claimants to perform the Schutztruppe manual of arms (weapons-handling drill). All 3250 who showed up to apply performed the drill correctly, more than 45 years after being demobilized.

The War in Africa

The centennial of the Great War has prompted a number of retrospective examinations of the effect of the war on Africa and of Africans' contributions to the war efforts of their colonial rulers. One effort to document the war's effect on the continent is

World War I in Africa.

The website provides some background to the project, founded by a French

geographer and a Tanzanian cultural activist, but overall the site

appears sporadically maintained. Their

Tumblr blog appears to be updated more often.

Another source is the

Great War in Africa Association.

Other pages include:

For a broad review of the Great War campaigns across the African continent,

Wikipedia's page is as good a place to start as any. In future posts, I'll look at some different African campaigns individually.

|

| Schutztruppe soldiers in Dar es Salaam (CNN) |

No comments:

Post a Comment